Yaqeen Hamad Jannoud

Academic lecture, Sultanate of Oman

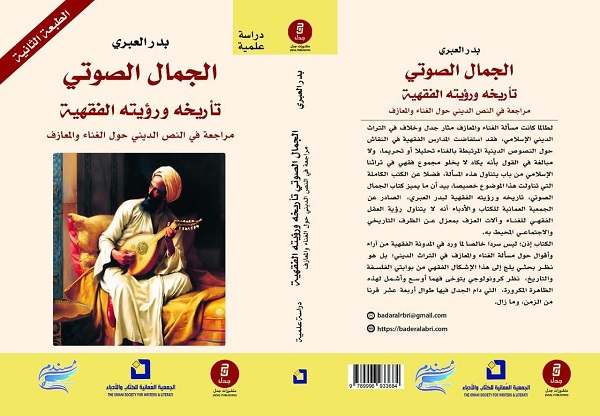

Shaykh Badr Al-Abri presents an encyclopedic intellectual project that seeks to reread the issue of singing and musical instruments outside the logic of ready-made rulings, and beyond the sharp binaries that for so long have reduced art to either absolute prohibition or unrestrained permissibility. The author does not approach singing as a purely juristic question, but rather as a human, aesthetic phenomenon that has accompanied humanity since the rise of civilizations, shaped by the formation of social life and colored by the diversity of cultural and religious contexts.

The book begins with a theoretical introduction that lays the foundations for the concepts of art and beauty as values deeply rooted in human nature. It then traces the historical development of singing and musical instruments from ancient times, through the pre-Islamic era, the Prophetic period and what followed it, up to the modern age. This survey is not presented as a neutral historical narrative alone, but as an essential background for understanding how juristic positions were formed, and how texts interacted with customs and with social and political circumstances.

Al-Abri shows that singing in the pre-Islamic period was part of the Arab cultural fabric, closely linked to poetry, collective memory, and modes of expression, without moral condemnation in itself, but rather judged according to its content and context. With the advent of Islam, the author demonstrates—through a careful examination of the texts and the Prophetic biography—that the Prophetic era did not witness an explicit prohibition of singing. On the contrary, it acknowledged it on occasions of joy and celebration, while regulating practices associated with licentiousness or corrupt amusement. After the Prophetic period, he traces the development of singing in the Umayyad and Abbasid eras, during which musical schools flourished and art intertwined with politics and society. He points out that the emergence of prohibitive discourse was, in many respects, a moral and social reaction more than a definitive ruling grounded in explicit texts.

The book does not neglect the local dimension, offering an important reading of Omani heritage and history that reveals the presence of singing in the Omani environment and the diversity of attitudes toward it—thus dispelling the illusion of a rupture between religiosity and art. It also employs civilizational comparison by examining the European Renaissance, showing how singing moved from the realm of mere entertainment into fields of science, therapy, and education—without fascination or projection, but in service of the broader vision that links art to its human function.

In its juristic section, Al-Abri adopts a broad comparative methodology, reviewing the positions of eight legal schools: Ibadi, Zaydi, Jaʿfari, Hanafi, Maliki, Shafiʿi, Hanbali, and Zahiri. He analyzes the evidentiary arguments drawn from the Qur’an and the Sunnah, distinguishing between the indication of a text and its authenticity, and between prohibition in itself and prohibition due to external factors. After scrutinizing the narrations and critically examining their chains of transmission, he concludes that the juristic disagreement over singing is based on ijtihād rather than certainty, and that there is no explicit text of definitive authenticity and meaning that absolutely prohibits singing and musical instruments.

The horizon of the book expands further in the section on aesthetic philosophy, where it discusses the concept of beauty in the Qur’anic perspective and traces the philosophy of beauty in singing across the ages. It draws on the views of major thinkers and scholars such as al-Ghazālī, Ibn Ḥazm, the Brethren of Alssafa, al-Shawkānī, Rashīd Riḍā, Shaltūt, al-Qaraḍāwī, and others. Through this presentation, the book establishes a central idea: that beauty is a legitimate value, not the opposite of religion, and that art—when understood in light of higher objectives (maqāṣid)—can be a means of psychological and social uplift.

In its contemporary applications, the book discusses the presence of singing in education, therapy, media, religious rituals, and in the lives of women, children, and youth, proposing ethical guidelines instead of absolute prohibition. It emphasizes that changes in time and place affect rulings, and that singing today is no longer confined to the forms of amusement known in the past, but has become an educational, media, therapeutic, and national tool.

The book’s final conclusion crystallizes in a clear and balanced position: the default ruling on singing and musical instruments is permissibility as long as it is governed by ethical and legal guidelines; absolute prohibition is not supported by definitive evidence; and musical instruments in themselves are not prohibited—the ruling depends on their use. The author also criticizes sweeping generalizations and unwarranted severity, seeing them as contrary to the objectives of Islamic law, which came to preserve the human being and the beauty of life, not to suffocate innate human nature.

In all of this, Badr Al-Abri does not offer a dry juristic manual, nor a historical study detached from its legal context, but rather an intellectual and aesthetic journey that restores balance between text and reason, and between authenticity and modernity. The Aesthetics of Sound is a distinctive reference in the jurisprudence of Islamic arts, an important document in the path of intellectual renewal, and a book that does not impose an opinion so much as it trains the reader to think—respecting both mind and heart together.

The book is a foundational reference for researchers in Islamic jurisprudence, the philosophy of art, and the history of Arabic music.