By: Muslim Al-Kathiri

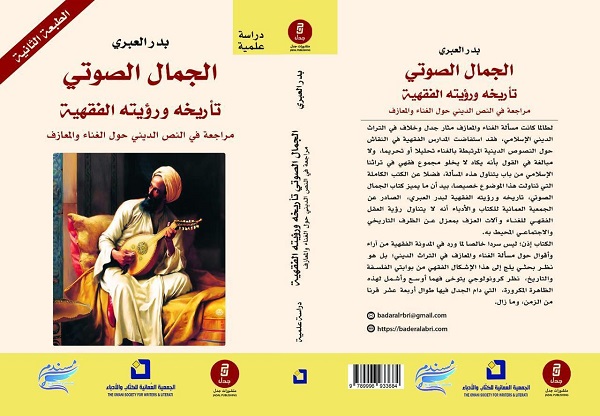

In this cultural essay, I attempt to shed light on the highly delicate task undertaken by Badr Al-Abri: formulating an illuminating aesthetic-juridical vision for the arts in general—and for music in particular—that differs in a genuine and substantial way from the traditional juridical view long prevalent in Oman.

From this standpoint, I wish to highlight the importance of Badr’s intellectual efforts, his objective and realistic methodology, and the need to further develop this approach in research, writing, and practice. On this occasion, I also call for transcending the rigid legal opinions concerning music and singing, including the historical terms and concepts such as “entertainments and distractions (al-malāhī wa-al-lahw)”, which tend to be static and dismissive of the artistic value of music—both vocal and instrumental.

Some jurists confined themselves for centuries within certain transmitted reports—reports that are, at the very least, subject to disagreement and whose authenticity is often uncertain. As a result, they fell behind in contributing to the formation of Arab-Islamic aesthetic and artistic thought and practice—an endeavor that was instead carried forward by Arab philosophers and theorists who played a significant role in the development of musical art and the crafting of musical instruments, not only in Arab-Islamic civilization but also in Europe and across the world.

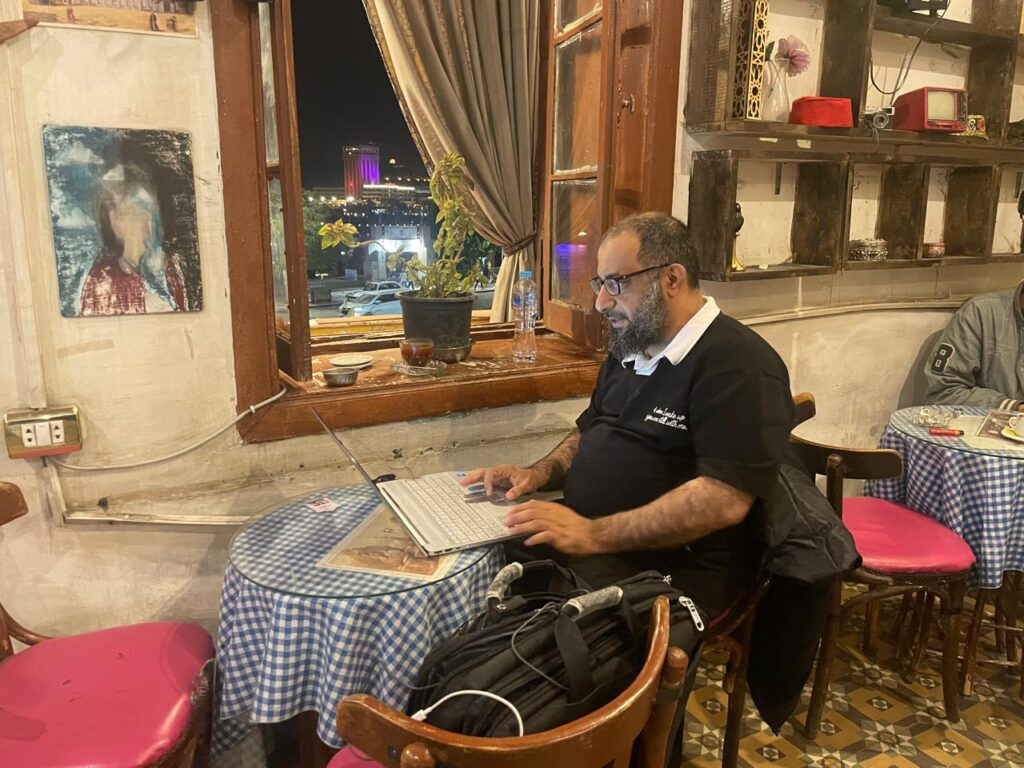

Badr is a striking example of the deeply humble Omani character. He is widely knowledgeable, highly active, and constantly engaged in research. His quest for what he calls “sonic beauty” begins, as he explains, from the Qur’anic verse: “Say: Travel through the land.” «قل سيروا في الأرض” ، For the more a person journeys through the world, the more their understanding expands — as he expressed in one of his radio interviews.

I listened to the summary of his book—recorded in his own voice—in which he surveyed part of the history of singing and music as a human phenomenon. He then moved on to discuss various theories and philosophies regarding the arts and music, before presenting in detail the arguments and positions of jurists across all Islamic schools of thought, including the Ibadiyah school. He concludes this survey with his own perspective that singing and musical instruments are matters of differing opinion since the time of the Prophet’s to the present day. On this issue he states: “When we contemplate the evidence, as shown earlier, we find that the proofs allowing music are closer to the spirit of the Sharia and farther from forced technicalities.” He also adds (with brief paraphrasing): “The early Ibadis… saw no harm in beating the drum, though they did not permit it for idle entertainment. Some also allowed listening to the large flute—the mizmar.” Although this view may appear narrow and strict, I understand it within its very different historical context. Nevertheless, the idea can be developed and renewed in accordance with contemporary musical practice, informed by modern theories and artistic applications. What Badr proposes clearly falls within this reformative framework.

Music is not criticized for its essence, but rather for certain behaviors that may sometimes accompany its practice. If we were to apply this same rule consistently, criticism would extend to almost everything we engage with in this worldly life. In my view, the jurisprudence of music and the arts remains behind the realities of lived experience. Traditional thought in this field tends to be either overly stringent or cautiously trying to catch up with numerous changes—without ever getting ahead of them. But Badr Al-Abri has taken a bold step and spoken what he sees as true, in harmony with human nature and the reality of life. He has taken into account historical developments and the diverse functions of music in our contemporary world, where dedicated institutions have been established, practitioners have multiplied, instruments and modes of musical expression have diversified, and artistic practices have evolved. Moreover, music today is a cultural industry and a fundamental component of visual and audio media, education, culture, and tourism.